Posts tagged with '.NET'

The principle of least surprise (sometimes known as the principle of least astonishment in more posh circles) is an axiom of design: typically UI design, but also software design. The idea is that some object, operation, device, etc, should be obvious and consistent with its name/appearance. A trivial example: a "left click" should be done by pushing the button farthest to the left on the mouse. To do otherwise would be quite surprising, and make for a bad experience. (That sounds shockingly simple, but it's just an example).

I was thinking about this when I was writing some validation code. I was thinking about a user selecting a U.S. State in a dropdown. On some forms, it's required for the user to select a State, on other forms it's optional.

I wrote a class to help me manage a list of States/Provinces like so:

Elsewhere, I wrote code to use the IsValidState method to check to see if the user, in fact, selected a valid state or not. The first time I did this, it was on a form where the field is required. So, if user doesn't select a state, then IsValidState wouldn't even get executed.

But, later on, I reused IsValidState on a form where the state field is optional. What happens when the state argument is null? A big fat exception, that's what. So, I changed the method:

Is that the correct decision? Or should IsValidState only be called when there's an actual value? I think I made the correct decision, because null isn't a State. Another decision that could be made is throwing an ArgumentException if the argument is null or empty. However, I don't think the correct decision was to leave the method the way it was.

So now let's enter the land of hypotheticals in order to think more about the principle of least surprise.

What if, instead of being a boolean function, IsValidState instead acted upon a StateArgs object being passed in (and its name was changed to ValidateState). Let's suppose there is some reason for this, and that part of the design is a given. Suppose there's a Value string property with the State and an IsValid boolean property. (ASP.NET Validators, specifically CustomValidators, work like this: the validation method get an "args" object, and you can act upon it by manipulating args.IsValid). What would the correct behavior be then if args.Value is null? Clearly, args.IsValid shouldn't be set to true. So, should it be set to false, or should it just be left unchanged?

In this circumstance, ValidateState is probably one method call in a series of validation method calls (probably with some polymorphism involved with the parameter instead of a specific StateArgs class). So it seems like the least surprising thing to do would be to not make a decision (option A in the above source code). Since ValidateState does not return a value, it's not required to make a decision.

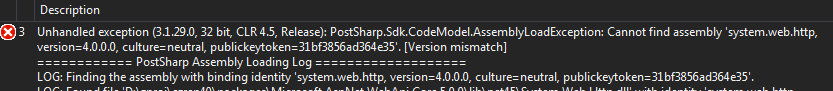

I was recently updating an ASP.NET project from MVC 4 to MVC 5 and I ran into some issues while compiling. The PostSharp post-compiler was complaining that it couldn't find a 4.0.0.0 version of an assembly.

I had the correct bindingRedirects in the Web.Config. I'm not completely clear on how and why bindingRedirects work, but as I understand it, this will redirect the compiler looking for a certain version of an assembly to another version of an assembly. Something like this:

I wasn't the first to run into this issue: I came across a similar question in the PostSharp support forums. PostSharp needs to be told where to look for the bindingRedirect confirmation (since PostSharp isn't specific to the web, the configuration could conceiveably be in app.config, web.config, or some other config file). So, I merely needed to add a PostSharpHostConfigurationFile property to the csproj file, as shown in the PostSharp documentation. After that, everything worked fine.

Ack, WebForms! Burn it with fire!

WebForms is known to be a horrible ghetto full of HTML pitfalls, a Kafka-esque lifecycle, testability nightmares, and pages served up with inflated ViewState data.

Some of that is still true, but WebForms has improved, and despite all the horrors that we're familiar with, it's still got a lot going for it, including a control tree that can be very useful at times.

I have been working on a WebForms project in my independent consulting practice (it sounds so fancy when I say it like that). Even though it's a relatively small project, I was still thinking about how best to introduce dependency inversion [PDF] to the project (or if I even should).

I googled around, sifted through a lot of ancient blog posts, and I came up with a relatively simple solution with my favorite IoC tool, StructureMap. It's not really optimal, or terribly elegant, but it just might get the job done and still allow us to write tests. I'm certainly open to alternatives, but because this is a small project, I don't want to spend a ton of billable hours on a solution, especially when I'll be turning the code over to novice programmer(s) when my time is done.

First, I simply add standard StructureMap config to the project. Application_Start in Global.asax is as good a place as any. I also use the default convention (if you aren't familiar, it's basically naming the interface by prepending an "I" to the concrete class name).

Okay, so that's pretty standard. Now let's approach from the other end: an actual code-behind class of an ASPX page. I can't use constructor injection here, because I don't have much control over this object being instantiated. Instead, I'll just make public properties for my service(s).

So now I've got a StructureMap defintion, and I've got properties that want to be set by StructureMap. But how do I get them talking? My solution was to introduce a base class (bleck) to the WebForms page. In this constructor, I'll use StructureMap's BuildUp method to populate properties (I have to specify which ones, as noted later on).

That's the ugliest part, as far as I'm concerned, but I couldn't think of a better solution. Maybe an HttpModule or something? Maybe the newer WebForms releases contain something that I'm not familar with yet? Leave a comment with your suggestions.

Finally, StructureMap just won't go and set every property by itself. You need to specify which ones. There are a couple of ways to do this. One is the SetAllProperties, which allows you to conditionally examine the PropertyInfo, and the other is FillAllPropertiesOfType, which you can use to directly specify which properties to set based on what type they are. Even though it's a small project, I'd would prefer to use SetAllProperties, so I don't have to go back and edit my StructureMap config each time I create a new service or a new WebForms page.

This week, there's a Manning Publishing promotion brought to you by my friends at PostSharp! This week of deals will bring you 50% off of a whole bunch of great .NET and/or AOP related books, including mine. You'll also get free excerpts from each book, so you can try before you buy.

Today, you can get my book, AOP in .NET, for 50% off, using code dotd0819au.

These are the Promotional Codes that will be active all week:

Day One: Save 50% on C# in Depth, Third Edition and Real-World Functional Programming. Enter pswkd1 in the Promotional Code box when you check out. Expires midnight ET August 20. Only at manning.com.

Day Two: Save 50% on AOP in .NET and AspectJ in Action, Second Edition. Enter pswkd2 in the Promotional Code box when you check out. Expires midnight ET August 21. Only at manning.com.

Day Three: Save 50% on ASP.NET MVC 4 in Action and ASP.NET 4.0 in Practice. Enter pswkd3 in the Promotional Code box when you check out. Expires midnight ET Aug 22. Only at manning.com.

Day Four: Save 50% on Metaprogramming in .NET and DSLs in Boo. Enter pswkd4 in the Promotional Code box when you check out. Expires midnight ET Aug 23. Only at manning.com.

Day Five: Save 50% on Brownfield Application Development in .NET and Continuous Integration in .NET. Enter pswkd5 in the Promotional Code box when you check out. Expires midnight ET Aug 24. Only at manning.com.

Day Six: Save 50% on Windows Store App Development and Windows 8 Apps with HTML5 and JavaScript. Enter pswkd6 in the Promotional Code box when you check out. Expires midnight ET Aug 25. Only at manning.com.

So, if you are a .NET developer, a web developer, or just trying to learn some more skills, this is the week for you!

Attributes in .NET are classes that derive from the Attribute class. Here's an example of an attribute as seen in ASP.NET MVC:

Attributes themselves don't actually do anything: they are strictly meta data. It's up to a framework or tool (ASP.NET MVC, WCF, PostSharp, to name a few) to interpret and use any code in or to infer any meaning from those attributes.

Attributes can have contructors, and you can use those constructors when putting an attribute on a class. But you can only use constant values (like a string literal, an integer literal, an enum literal).

You also can't use type parameters on an attribute, but you can use typeof() when using an attribute.

As I stated above, attributes don't actually do anything on their own. To see what attributes are applied, use Reflection. For instance, to get attributes set on a class: